MASTICARE: Roberto Chabet

Carina Evangelista

Chabet chews.

Chew Chabet.

Chew the word masticare, Latin for “to chew” and one comes up with the following anagrams:

Marciaste – second-plural past historic of marciare (to walk)

Macerasti – second-person singular past historic of macerare (to macerate, to soak)

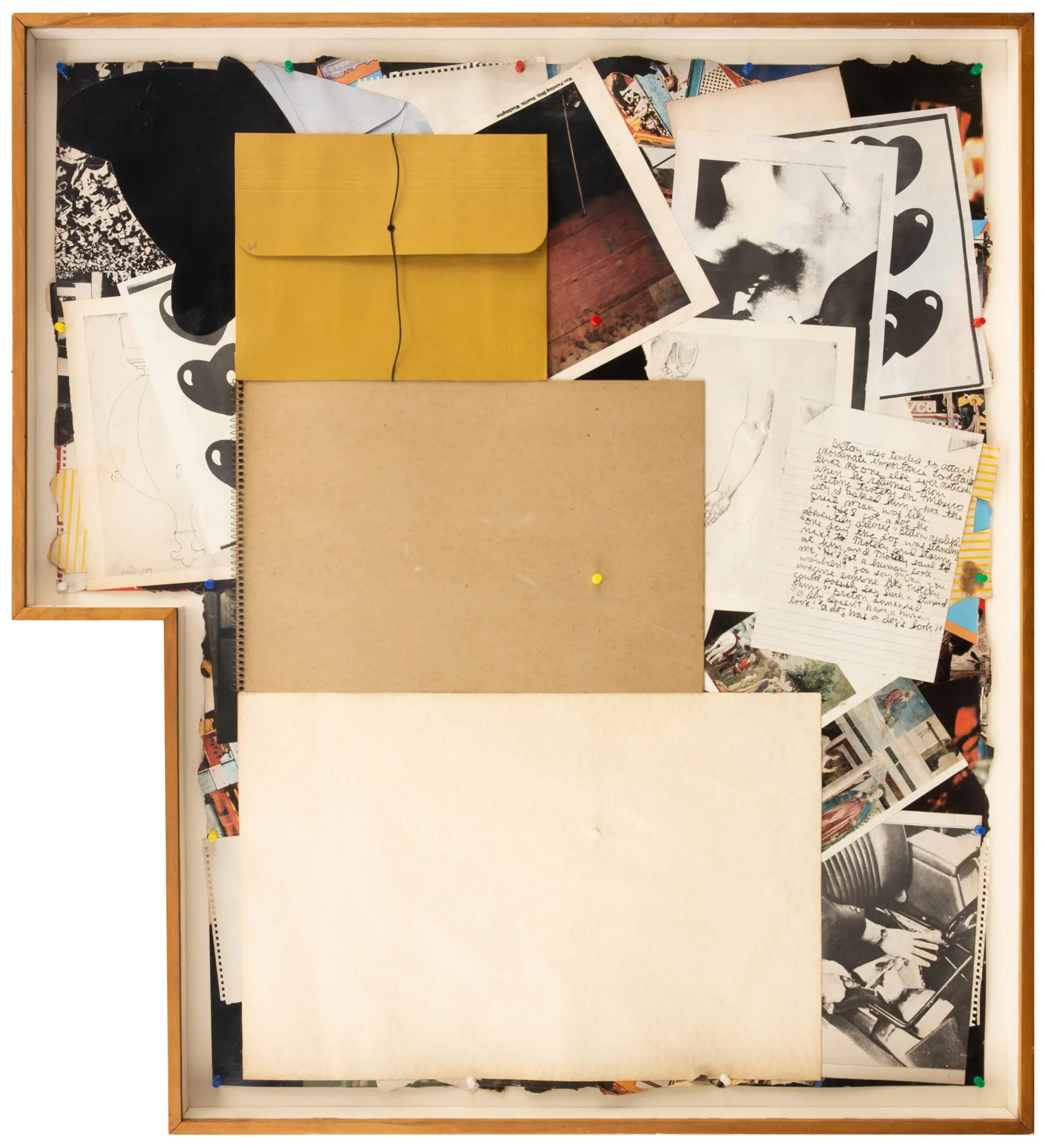

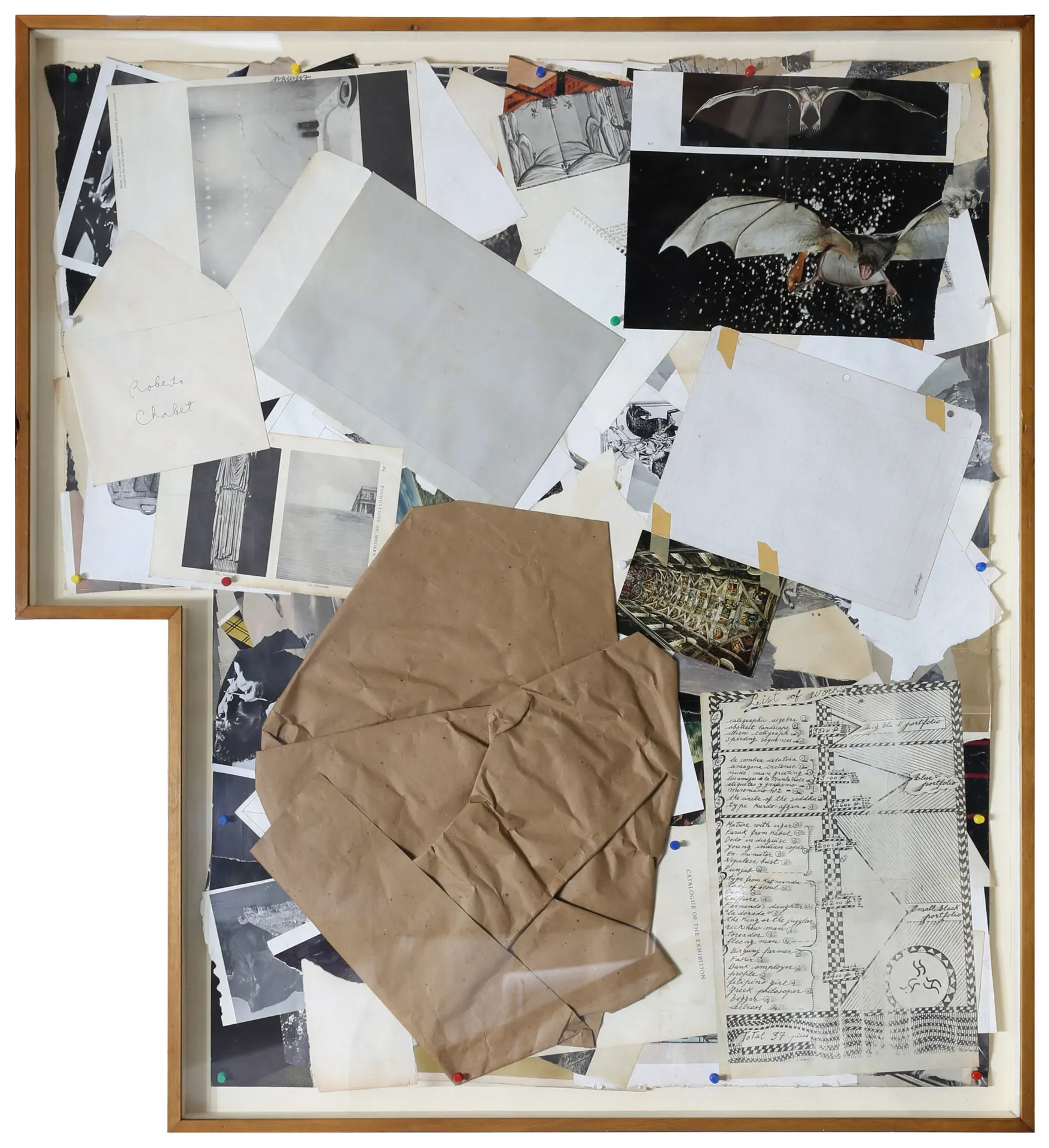

Of all his works, nothing demonstrates the ravenous and the ravished more than Roberto Chabet’s sustained practice of collaging—methodical, maniacal, maddening, meditative, and altogether reflective of the monstrous and the marvelous of mad times. It was in 1973, just four months after Martial Law was declared, that the tinder for the China Collage series was lit, likely unbeknownst to the artist himself, with Tearing to Pieces, the legendary pile of ripped pages from the state-commissioned tome on Philippine contemporary art by Manuel Duldulao that Chabet exhibited at the Cultural Center of the Philippines. Five years on, the year that the CCP exhibitions were steeped in formalist abstraction while the country’s internal political tumult intensified, another touchstone collage came in the form of a series of panels of delicately torn white paper in 1978,[i] as if to serve as a visual palate cleanser before embarking on the China Collages (1980-1990, 1992, 2011). Chabet once alluded to a Mao Zedong quote from The Little Red Book, “On a blank sheet of paper free from any mark, the freshest and most beautiful pictures can be painted.”[ii]

And then the tidal wave of countless cut-out and hand-torn pieces of paper from books, newspapers, magazines, comic books, art students’ plates, maps, and stamped envelopes bearing witness to the wealth of visual material and the photographic march of history that the artist feverishly consumed, shredding with both love and violence as if each scrap bore a secret that could only be uncovered by chewing and spewing.

The China Collage series dares you—its hapless, seduced viewer—to look away. The colors, serrated edges of torn paper, body parts, and visual puns command you to look. To behold these collages is to be held captive by a suspicion that every single tatter—familiar or foreign—is sinister. It’s all just paper—plastered, tastefully framed, but far from benign. You identify things you think you know and cognition stuns you with the thought that you’ve trodden the terrifying terrain of a two-dimensional Mondo Cane.

The series is titled after the maps of China, Mongolia, and Korea Chabet bought at a bookstore and used as a base for many of the collages, with the overleaf of the opened map explaining their peculiar, inverted fat L shape. A grid of coordinates for islands, rivers, mountains, and paths served as the expanse subsequently smothered with layers of paper to create a topography littered with the thick confetti of chaotic visual information. The fixed latitudes and longitudes of orientation on the map are submerged in the surreal, kaleidoscopic swill of the artist’s voracious appetite.

Regurgitated from the mill of Chabet’s mind are visual morsels, an inventory of which would itself comprise a fantastic exercise—an attempt at entering each collage as if on a dérive (a psychogeographical concept of random urban exploration with the discovered aesthetic contours and ambient zones for a compass; literally translated in English as ‘drift’).

Drift into Chabet’s collages and you dredge up: a handwritten list of ingredients; a magazine list of armaments; the naked behind of a mannequin; an odalisque’s leg; a goat; a gargoyle; Incredible Hulk’s nose; the boot mark of man’s first landing on the moon; Piet Mondrian’s line drawing of a chrysanthemum; Picabia’s Portrait of Marie Laurencin, Four in Hand; a spotted cow; Elvis; Brigitte Helm in Lang’s Metropolis or Fay Wray in King Kong; a postcard of beautifully adorned Maasai women; Matisse bronze sculptures; a Roger Crowley chair; one-point perspective drawing of staircases and arches perhaps by the 17th-c. mathematician, Marolois; Jasper Johns’s painting of the US map; the US flag reflected on an astronaut’s visor; an unidentified flying object; early and iconic abstractions by Mondrian; swatches of the Zoner-Bloser cursive template; an aerial view of a boat pit alongside the Great Pyramid; Joan Miro’s ceramic murals for the UNESCO (Wall of the Moon and Wall of the Sun); Jackson Pollock’s signature; a page from a coloring book; Buddha; a bat in wet flight; a Dürer engraving; spires; vaulted ceilings; a temple in Tibet; old family photographs; Van Gogh’s Pollarded Birches with Woman and Rock of Sheep; Caspar David Friedrich’s Mountain Landscape with Rainbow; Carracci’s Flight into Egypt; a proliferation of WWII warplanes featuring the Messerschmitt cross or the swastika; a Kurt Schwitters collage;[iii]daubs of paint on a manual for mixing colors; photographs of a reclining nude from different angles; a photograph of the 1930 Sto. Tomas University Fair; the candy-colored musculature of superheroes; Matthew, Thaddeus, and Simon on Da Vinci’s The Last Supper; Minnie Mouse; shark teeth; ladyfinger cookies; an eagle; an onion, a taro root, and potatoes; a roller coaster; photographs and representations of the human figure.

Almost always just fragments, the human figure in Chabet’s collages can be seen mostly cropped—limbs; feet; pant legs; a female runner’s torso; a child’s curled toes; the foreheads of a couple locked in a kiss; hands; knuckles; intertwined fingers; fingers holding playing cards, knitting, or strumming a guitar. The open palms call to mind Soviet posters, the hand in Buñuel and Dalí’s Un Chien Andalou, and the Sieg Heil salute. One captioned photograph betrays its source. The caption reads, “The Mount of Mercury” (located at the base of the pinky finger), revealing that these photographs might have been from a book of palmistry. Another captioned open palm reads, “Hand of Criminal Type.”

The occasional human figure shown in full would be that of Piero della Francesca’s St. Sebastian, with his body pierced with arrows. As to the proverbial windows to the human soul, Chabet nods again toward Buñuel and Dalí with one large close-up of a woman’s eye ripped horizontally so that only the lower half of a gorgeous pupil and the lower lashes are visible; another pair of eyes is pasted upside-down, ripped right where the eyelids end and the sockets begin.

A few collages are predominantly white or black and white but even the white papers from sundry envelopes or book end papers sport patina specks of time in the stains, discolorations, foxing, and mottling. Others incorporate the shells of books and notebook covers, splayed like a carcass stripped of its contents.

These collages are the inverse of Jacques Villeglé’s décollage panels of the stripped layers of street posters taken directly from the street walls of Paris from the 1960s. The latter are subtractive transformations by “le lacére anonyme,” the countless anonymous hands that tore the posters. China Collages are a cumulative transformation of the desirée into the déchiré—a threshing of the treasured. Some torn pages still bear the puncture marks of thumbtacks, evidencing previous lives as bulletin board pinup specimen for study, fond regard, or critical rumination. Now torn, plastered in layers, and framed, these strips of paper so willfully ripped aren’t discarded but preserved. The composed visual detritus anticipates the mashup, suggesting that all—Buddha, Superman, and the swastika—are fair game or that the varying reds of a tomato, a Valentine, a dab of cadmium paint, a flattened McDonald’s pouch, and the Biblical burning bush are all equal in formal or allegorical value in a massively complex contemporary time where things indeed mash up into one chaotic mess with a missing vortex. But Chabet is not a mechanical shredder or food processor and the collages are not merely panels of indecipherable or pointless visual cues where the benign mingle mindlessly with the malignant. Of all possible iterations of the cross, it is the swastikas on those warplanes that predominate.

Consider the syntax of a small section where a sweet illustration of an American family with perfectly rosy cheeks and blond curls looking at the Nativity scene abuts a black-and-white photograph of weapon-wielding soldiers, the image torn off right at the soldiers’ chests rendering it simultaneously sinister and tragic. Men with guns without heads. Baby Jesus lies in his manger. A mysterious figure lies sprawled on a white bed in another adjacent scrap.

When reproductions of art and an assortment of banal things are interrupted with photos of warplanes, weapons, and disembodied anatomical parts, the visual Tower of Babel is not just what Robert Rauschenberg described as a “recognition of the lack of art in art and the artfulness of everything.”[iv] The coded diarrhea of this diarist is a running commentary—albeit mute. A barely coded review by Augusta de Almedda in 1981—in the middle of the Martial Law years—boldly referred to the early China Collages as “Assassination as the Artist’s Aim.”[v] The reviewer bluntly writes of the far-from-precious shreds of paper during a time of persecution of intellectuals and repression of dissenting political voice:

Chabet’s poison arrow aims itself at [the] looker—peer? critic? art patron? art collector? the moneyed culturati? Whose one claim to art is not its understanding or its appreciation, but the ability to purchase art with its attendant gaudiness of prestige and cultural snobbism—the temper of the times, after all, believes in the trappings of culture. But culture not when it remains the handmaiden of art, which is the aristocratic domain of the noblesse oblige, but culture when it can be bandied around like a silk crepe de chine Dior, or a Ming [vase] sitting in some arcanely ornamented parlour of the new rich.[vi]

This was not a time of idyll or romance. What compels an artist reported by Marian Pastor Roces as having been described as one who “eats art, reads art, speaks art, fucks art, defecates art”[vii] to ensnare the art he supposedly inhales and exhales with reverence within a field rife with the sinister, the menacing, and the downright sordid (an image of maggots crawling over a decomposing corpse) if not to posit the reality that one’s purest joys and deepest fears cannot be impervious to one another? That love and squalor embrace?

De Almedda adds:

Chabet keeps the mental sores ever inflamed, to foment the irritant that will yield art born[e] of the artist’s disgust with himself and his environment—this, contrary to the ignorant belief of non-artists that the artist needs to be happy in order to be inspired to create well.

Backtrack from 1981 to 1976, Chabet’s collages were smaller in format but no less mordant. One bears a torn page from an essay, A Dissertation Upon Roast Pig. Text that could be read from this page starts with “her—like lovers’ kisses, she biteth—she is a pleasure bordering on pain from the fierceness and insanity of her relish—” and in the next paragraph, “Pig—let me speak his praise...” Another collage comprised of black-and-white magazine or newsprint cutouts features three main items: a fresco depiction of Dante’s inferno “with Satan seated at the centre;” a photograph of nearly naked children standing in a semicircle, blindfolded and with arms raised high; and an archival photograph of the execution of an I.R.A. rebel in 1916. Yet another features torn scraps of reproductions of Oriental tapestry adorning an undergrid of newspaper cutouts that include a line drawing of a Crucifixion; an architectural drawing of a marble-topped, Baroque credenza; a photograph of stately Nazi flags from the book Architecture and Politics in Germany 1919-1945; and an archival photograph in a newspaper article of a Filipino being garroted with a caption that reads, “Strangulation in Manila.”

If Chabet’s collages defy you to look away, they also beg to be read. Your eyes scour the panels for visible captions so that comprehension might serve as lifeboat. A sampling of these disparate words—from book pages, comic strip speech balloons, or written in ink—includes:

Restless, in pain, anxious, and afraid.

A hot ember seared my ankle.

DRACULA

HOPELESS

GR-R-R R-R

HELP! HELP!

These collages channel the horror vacui aesthetic, the dérive maneuver, the affichiste design. But put aside all these foreign words and concepts; put aside all words altogether; and look, simply look. One gasps at the visual resonance of Chabet’s collages from decades ago with photographs of the wreckage in the wake of the tsunami that hit Japan in 2011, the year that this essay on China Collages was first published, or in the wake of any other disaster—natural or manmade.

The maps that serve as the base for these collages were so cheap they were practically being given away for free when Chabet bought them. Between 1980 when Chabet began this series and now, so much of the history that unfolded in these countries has changed. It was also in 2011 that the administration of President Benigno Aquino III began to refer to the part of South China Sea that is part of Philippine territory as the West Philippine Sea, to assert the country’s sovereignty over the waters still being aggressively claimed by China to this day despite the 2016 arbitration under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea that ruled in favor of the Philippines, declaring that China has “no historical rights” to this area. China’s claim on the entirety of South China Sea has repeatedly surfaced in popular culture over the years with the subliminal yet deliberate and calculated inclusion of the arbitrary nine-dash line in maps that have curiously appeared in the DreamWorks animated film, Abominable; a number of Netflix TV series; the website of South Korean girl band, Blackpink; and even the popular 2023 film, Barbie, triggering calls for boycotts or outright bans in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Vietnam.

Chabet, who died in 2013, did not live to witness the incursions with sand piled on existing reefs, killing the coral and endangering marine biodiversity, as well as ports, military installations, and airstrips constructed. The Chinese Coast Guard has used fired water cannons against Philippine ships and the ongoing territorial disputes have resulted in the loss of livelihood for local fishermen.

Chabet could not have anticipated this conflict at such global scale when he decided to use these maps as substrate for what he himself has described as his “picture morgue” but the maps now buried under these layers of torn paper from random sources speak to how maps, as critical evidence in such disputes, might bear witness and therefore also fall victim to geopolitical transgressions that might condition the reinforcements or obsolescence of cartographic lines and coordinates. Among the torn book pages that stand out in one of Chabet’s China Collages is text that reads:

L’enfant pleure... Il est triste. Il pleure.

[Ang musmos ay lumuluha… Siya’y mapanglaw. Siya’y lumuluha.]

This essay, first published in Chabet: Fifty Years, in 2011, was updated by the author for the 2025 exhibition at MO_Space, marking Roberto Chabet’s 88th birth anniversary.

[i] This series of white paper collages could also have been a witting or unwitting reflection of the political “whitewashing” during the Marcos years, which served as Joselina Cruz’s thesis for an exhibition in 2002. Cruz wrote, “[Edgar Talusan] Fernandez remembers...that the murals they painted then would be gone the next day. Each one would be whitewashed. And so it went: for every political mural painted, the process of whitewashing took place. Expressions of protest would be erased under the cover of white paint.”

[ii] Taken from the unpublished transcript of Ringo Bunoan’s interview with Roberto Chabet and Joy Dayrit (Manila, July 3, 2008), p. 27.

[iii] Kurt Schwitters, on his periodical Merz (1923-32), in which his graphic collages appeared: “In the war, things were in terrible turmoil. ... Everything had broken down and new things had to be made out of the fragments; and this is Merz.”

[iv] Transcribed from the film Rebel Ready-Made: Marcel Duchamp (BBC, June 23, 1966), quoted in Francis M. Naumann, Marcel Duchamp, The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (New York: Abrams, 1999), p. 294.

[v] Augusta de Almedda, “Assassination as the Artist’s Aim,” WHO (Manila, 1981), p. 27.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Marian Pastor Roces’s report about this summation of Chabet having been “said in awe” by the quoted, unnamed observer appears in Judy Sibayan, “Problematizing Artistic Labor (The Failed Avant-Garde),” http://www.ctrlp-artjournal.org/hide/The-Failed-Avant-Garde.pdf (accessed March 28, 2011), p. 6.

About the Artist

About the Artists

The pioneering Filipino conceptual artist, curator, and teacher Roberto Chabet is known for his groundbreaking experimental work which ranges from paintings, drawings, collages, sculptures, and installations that harness the found and the ordinary.

As the founding Museum Director of the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Chabet (1937-2013) initiated the Thirteen Artists Award in 1970 which aimed to support young artists whose body of work expressed “recentness and a turning away from the past.”

Posthumously awarded the Gawad CCP Para sa Sining in 2015, he had taught at the College of Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines Diliman for over thirty years.

Related Exhibitions

About the Artists

About the Artist

The pioneering Filipino conceptual artist, curator, and teacher Roberto Chabet is known for his groundbreaking experimental work which ranges from paintings, drawings, collages, sculptures, and installations that harness the found and the ordinary.

As the founding Museum Director of the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Chabet (1937-2013) initiated the Thirteen Artists Award in 1970 which aimed to support young artists whose body of work expressed “recentness and a turning away from the past.”

Posthumously awarded the Gawad CCP Para sa Sining in 2015, he had taught at the College of Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines Diliman for over thirty years.

Related Exhibitions

Share