Visualize the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) in the early 70s and what comes to mind are the pomp and circumstance that heralded “Asia’s Mecca of the Arts”1—Leandro Locsin’s architectural wonder that literally emerged from the waters of Manila Bay on 21 hectares of reclaimed land. The cantilevered monolith, its marble slabs, water fountains, grand chandeliers, and large, plush tapestry curtain woven in Japan and based on H.R. Ocampo’s painting, Genesis, all make for a dramatic setting for “how to build a cement cradle and breed the new Filipino.”2

It was in the early days of this looming, cavernous, and stately building found to be a cultural marvel by admirers and a vulgar monstrosity by critics that Roberto Chabet installed directly on the floor of the CCP Main Gallery a grid of monays. Himself trained as an architect, Chabet eschewed the monumental for the homely monay. Row upon row of bread with their trademark slit down the middle—readymades assisted by the artist by painting them pink—mooned viewers from the floor like an army of gauche mouches (French for ‘flies,’ also the term for 18th century French false beauty marks made of small silk or velvet patches) on the handsome face of the wooden parquet floor of the most celebrated and protested example of Imelda’s edifice complex.

The artist reprises this installation at MO_Space in a work simply titled Bread as part of the yearlong series of exhibitions celebrating his 50 years as an artist. The 2011 monays have shed their Pepto-Bismol pink in favor of a matte varnish and acquired plinths of 10" x 10" mirror squares. As the floor of MO_Space is simply poured concrete, the mirrors approximate the grid points of the parquet floor at CCP and effectively serve as small squares of reflected light to offset the nutty-brown top crust of the bread from the concrete gray of the floor.

Bread utilizes four of the distinct and recurring features in Chabet’s body of work: the use of everyday objects, floor-bound installations, gridded seriality, and mirrors. Appointed as the first director of the CCP museum, he was first sent on an extensive travel grant to study museum management in France, Germany, India, Italy, the U.S., and the U.K. before his tenure, which he cut short when he abruptly quit within a year of the CCP inauguration. Interestingly, from such an auspicious exposure to the most prestigious museums in major cities around the world, Chabet filtered out the august, the opulent, and the fastidiously preserved in his own artistic practice. What seems to have resonated with him the most in his travels as an artist and curator are the rebellious spirit of Fluxus, the materialist sculpture and serial convention of Minimalism, and the attitude of Arte Povera in “flout[ing] the sanctification of huge exhibits”3 and its “critiques and debates on the constant reproduction of dogmatic and spiritualistic forms.”4

For the 1972 Summer Exhibition, also at the CCP, the young Filipino artists’ increasing use of commonplace things was lauded as a predilection for the nakedly real, contrasted to the adorned “lyricism of Luz’s cyclists, Magsaysay-Ho’s folks, Manansala’s jeepneys, Zobel’s ice cream vendors” and the “obscure expressionism” inherent in the latter which were literally labeled “sala-sleek merchandise.”5 This is in step with the Minimalist steely riposte to the indulgence of the abstract expressionist sublime or the Arte Povera renunciation of “art as a perfect and immutable instrument, that is, moving within the reassuring limits of the sacred icon” in favor of “an iconoclastic behavior and approach that heed the problems of real, actual existence and move in relation to the multiplicity of contexts and eras.”6 The Fluxus “revulsion for high formalist abstraction”7 is from the artists’ conviction that formalist abstraction “provided not art but preferred shares, not art but capital.”8 There couldn’t be anything more mutable and far from collectible-as-art than lowly pieces of bread placed directly on the floor.

The text for the 1973 CCP show, An Exhibition of Objects, expands on the fascination with the materially real in the everyday object by adding to its points of interest—beyond its fundamentally sensate physicality—“its visual wit” and its “natural power to arouse our associative faculties which would generate corresponding associations.”9 Bread is the most common metaphor used for sustenance from “the bread and butter” that we earn to the enriched brioche that Marie Antoinette wanted the starving masses to eat and the daily bread that we implore God the Father to give us. As an economic barometer, a revolution trigger, and spiritual fodder, it is a unit of measure.

Meanwhile, the monay is distinct for its cleavage, giving the impression of a well-endowed bosom and giving the word ‘buns’ their pastry form. Supposedly the Filipino version of the Spanish pan de monja or nun’s bread (with another pastry variation, suspiros de monja, nun’s sighs), the bread’s form has more likely been christened monay not as a modification of the word ‘monja’ but for the more risqué resemblance to the vagina, the Ilonggo word for which is precisely that: monay. The dough is kneaded to the desired texture and then given a deft cleft on top after it has risen. For our visual, culinary, and imaginary delectation, it is a unit of pleasure.

Arranged in a grid of rows, each monay is indeed a unit within a visual matrix of measured points, uniform and thus staccato in rhythm. But like all things arranged in a serial grid, it is not about the exact number of components. The 12 rows of 10 monays each total 120. But these staccato points or punctuations are not quite finite or conclusive as periods, but comprise a continuum as ellipses. The square mirrors they sit on slice and incise the concrete canvas; fragment and multiply the space; interrupt and extend the visual field within the white cube of the gallery. If, contrary to architectural ideals of towering permanence, this artist privileges the prostrate ephemeral, he at least alludes to multiplicity and, in the case of ease in reconstructing a work long gone forty years later, to renewal and continuity.

Carl Andre’s 144 Blocks & Stones (1973) bears formal kinship to Chabet’s tableau but the latter is more akin to the Nepalese chaityas (roadside altars). The organic in bread makes it a living thing, and thus also a dying thing, much like the altar offerings of fresh fruit, flowers, and incense that inevitably evanesce. Andre’s concrete blocks and river stones—dedicated to Robert Smithson who died shortly after 144 Blocks & Stones was completed—have the more definite memorial permanence of stone slabs and grave markers.

Chabet in fact attempted to preserve the original monays, each wrapped in foil. Opened many years later, he discovered the crusts completely intact by dint of the pink paint coating, but they were also completely hollow as ants had eaten them all up from within. Fluxus works were described by Robert Pincus-Witten as “apt to be temporal,” as objects “in small scale dedicated to the transient aspects of the human enterprise” and wont to “sour and spoil, crumble and crack, go limp..., cannibalize themselves and mestastasize...”10 He also refers to the Fluxus spirit as “ambitiously experiential and unabashedly existential.”11 Think about it. The ants that transformed Chabet’s readymades by feeding on them have themselves died, the carapace of their little bodies having turned to dust. Ars / vita brevis: of brittle shells and fleeting life.

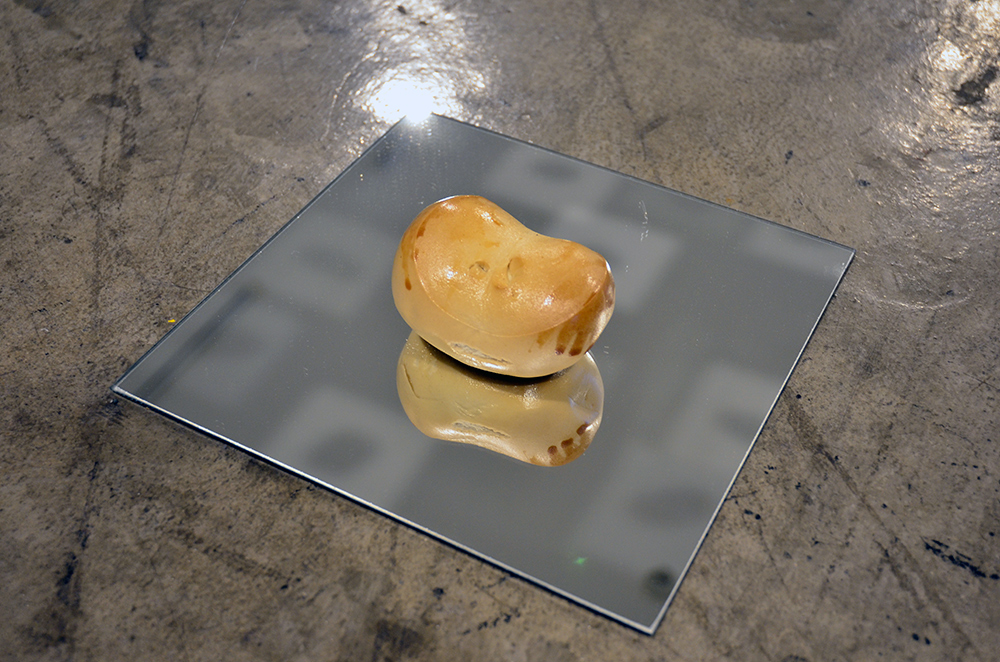

In the small video room at MO_Space, a lone monay, cast solid in iron, sits on a 2' x 2' mirror also laid on the floor. It bears noting that these mirror plinths come very thin at 1/8". Chabet wanted “the weight of cast iron to interact with the fragility of the mirror.”12 While the real monays in the larger gallery are lacquered with clear varnish to protect them from insects, the cast iron version is left untreated so that, exposed to the elements, it develops a patina. Cast iron is known to rust at a relative humidity that exceeds 64%. The work becomes precious not by virtue of measures taken to keep the art object pure and preserved, but by virtue of its mutability. Time and air, things we cannot touch but inescapably touch us, will touch the object, corrode it, and coat it with their imprint. Casting bread in iron is making a permanent monument out of an organic morsel. At the time of this writing, record for Manila humidity is at 75%. In this case, the sculpture, whether it is touched by our gaze or not, and despite being cast in heavy metal, is already and irrevocably transforming at the mercy simply of being.

1 Pedro R. Narvasa, “The Cultural Center of the Philippines: Asia’s Mecca of the Arts,” Business Chronicle, 31 May 1970.

2 Print ad for Filipinas Cement that accompanied the feature article of Pedro R. Narvasa on the Cultural Center of the Philippines as “Asia’s Mecca of the Arts.”

3 Germano Celant, “1968 An Arte Povera / A Critical Art / An Iconoclastic Art / Knot Art 1985” in Celant, The Knot: Arte Povera at P.S. 1 (New York: P.S. 1, The Institute for Art and Urban Resources and Turin, Italy: Umberto Allemandi & C., 1985), p. 7.

4 Celant, p. 10.

5 Notes on Summer Exhibition (Manila: The Cultural Center of the Philippines Library, 1972).

6 Celant, p. 9.

7 Robert Pincus-Witten, “Fluxus and the Silvermans: An Introduction” in Jon Hendricks, Fluxus Codex (Detroit, MI: The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection and New York: Harry N. Abrams Incorporated, 1995), p. 16.

8 Ibid.

9 Notes on An Exhibition of Objects (Manila: The Cultural Center of the Philippines Library, 1973).

10 Pincus-Witten, p. 16.

11 Ibid.

12 Roberto Chabet in a text message to artist / curator Nilo Ilarde, as emailed to the author by artist Mawen Ong, August 25, 2011. Chabet was very specific about casting the monay in iron and not in bronze, so as to draw associations not with art but with plumbing. This can be read as a nod to the Dada irreverence of Marcel Duchamp, who famously pronounced “The only works of art America gave are her plumbing and bridges.” Duchamp gave the world “Fountain” (1917), an inverted urinal, whose companion piece is Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s “God” (1917), a cast iron plumbing trap mounted on a miter box that nearly a century later remains profoundly blasphemous, resisting the artistic beauty that art historical time might allow. More specific to the Philippine context, the plumbing connotation is also kin to Danny Dalena’s pozo negro installation at a Shop 6 exhibition in the early 70s, recently recalled by Chabet during the artists’ discussion of Shop 6 activities held at the Lopez Memorial Museum.