Everything is Sacred

Norberto Roldan

15 – 21 September 2009

Curated by

15 – 21 September 2009

SUPER BEINGS, SUPER HEROES, AND SUPER SEMANTICS

Lurking in a statement by Philippine writer and curator Emmanuel Torres lies the foundation upon which Norberto Roldan’s work springs.

Central to this exhibition is a reworked piece that perhaps best illustrates this sense of accumulation or chameleon layering, Objects and Apparitions (2006–2009). First shown at the Alliance Française de Manille (2006), its two domestic shrines were presented, backed by a projection of the film Hiroshima, Mon Amour by Alain Resnais. As objects, the altars are familiar to our everyday, making them relatively benign, and yet when presented at eye-level and placed within a gallery environment, they become quiet, provocative, and charged in the context of the film. One wonders whether the object’s transformation from sacred to profane reflects the truncated pace of our digitized world, as fragments dramatically caught on-screen. Roldan elaborates, “...in the context of contemporary geopolitics, religion has been used so many times—either to wage war or to sow terror, both anathema to almost all religions or religious tenets.” It is the reality of a post-9 / 11 world.

This metaphor of media illumination is perhaps best illustrated by the second presentation of Objects and Apparitions for Roldan’s 2008 solo exhibition at Manila’s MO_Space. Here the altars were filled with light, their sacred enlightenment provided by a hardware-store bought floodlight and playing off the ping of conceptual triggers. Propagated terror had been replaced by the most banal of objects. The presentation of the two shrines at TAKSU, however, is perhaps the more revealing version.

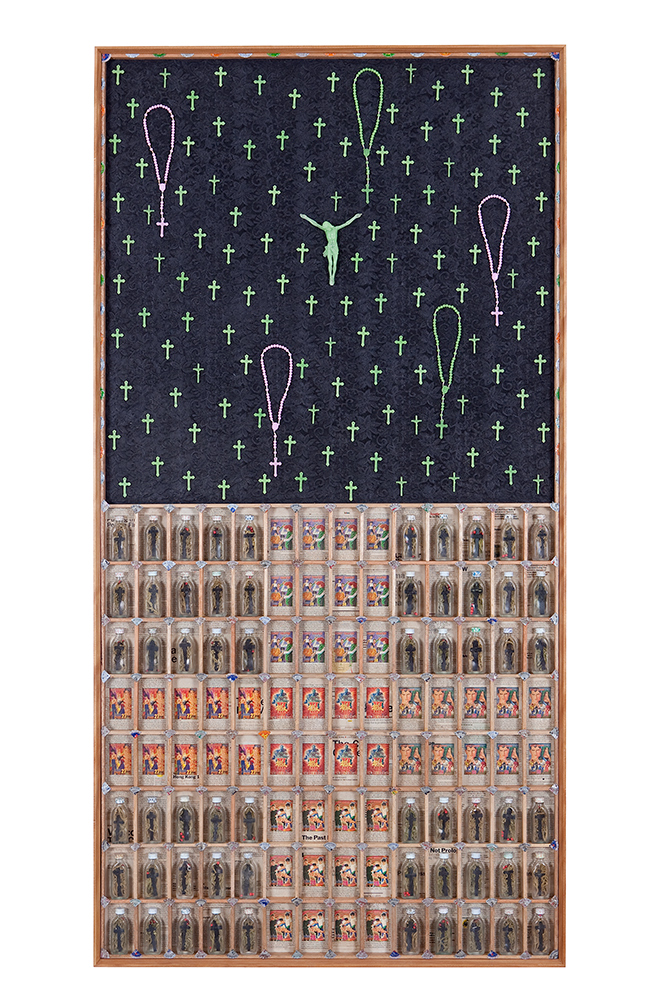

Filled with objects collected during Roldan’s stay in Malaysia, they became vessels of pan-religiosity corralling humanity ‘under one roof.’ Roldan engages the metaphoric possibilities of common, locally available objects to reflect upon the shifting constructions of order, categories, and meaning. It is an astute picture of contemporary Asian society in flux. In the same way that Objects and Apparitions tethers Roldan’s career across a 3-year span, two suites of assemblages in the genre of American Joseph Cornell capture Roldan’s ability to siphon an object’s ability to communicate across time. Roldan’s “Memory Boxes” take their cue from his 1999 exhibition Faith in Sorcery, Sorcery in Faith at Hiraya Gallery, Manila; and perhaps more familiar locally, his work in the Singapore Art Museum collection.

Housed in Cuban cigar boxes, Roldan plays off cerebral and emotive triggers plucked from a database of objects: estampitas (holy pictures), anting-anting, and bottles of native ‘remedies,’ metal amulets, faded photographs, and plastic superheroes. It is symbology as energetic and popularist as a Dan Brown novel, oscillating between folk religiosity and popular culture with the efficiency of a haiku.

While the cigar box may whiff of nostalgic eyecandy as a mini menagerie, it also points to agri-politics—of Cuban contraband paralleling a local tale of Philippine tobacco industries used as leverage for political concession. The truth is, Roldan’s cigar box is just an available object found in a thrift store. It is our compulsion to lay meaning over objects and images that blurs truth.

What emerges repeatedly across these two exhibitions, Everything is Sacred (TAKSU Kuala Lumpur) and Profane is the New Sacred (TAKSU Singapore), is not the particularity or endorsement of religion as a power-base, but the sense of questioning what we hold sacred in contemporary society. The object has become increasingly aspirational, manufactured, and disposable. The ability to trans-locate it and yet maintain its veneration—whether celebrated by an adult who grew up on Power Rangers in Manila, a 6-year Malaysian boy hip on Transformers, or an Australian kid who believes in both Santa Claus and Jesus—reiterates the ability of visual media to communicate collective belief in the ‘unbelievable.’ As Roldan’s title suggests, ‘profane is the new sacred.’

The “Sacred Devotion” assemblages were reworked from an earlier installation “Private Altars” (2003), commissioned by the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum. It was originally aligned along a 10-meter table dressed with lace altar cloths and capped off with lightboxes of Latin text; for this exhibition, Roldan has encapsulated the altars in vitrine-like museum cases. I am reminded of Thai traveling icons that house their devotions in small wood shrines worn around the neck or carried in a pocket. That sense of the mobility of divinity has a currency with ‘the box’ as a shipping device—from aspirational white goods to Philippine Balikbayan boxes that carry a domestic worker’s most treasured belongings between countries. The vessel itself becomes loaded with association. Box or grid, our human compulsion to collect, order, file, locate culturally, digest, and assimilate visual iconography is an interesting one when overlaid with the semiotics of ‘a frame’ that is boxed-in, pigeon-holed, quarantined, defined, or to use Roldan’s word, rendered “sacred.” It moves well beyond the realm of religion or identity politics.

In the same way that Roldan has adopted ‘the container’ to present his work, he has long included found photographs in his art-making: from his assemblages to large-scale digital banners, and more recently, manifesting as photo-real painted images. For this reason, I find the new series included in this exhibition, We Have Nothing That is Ours Except Time and Memory, is grid formation and sense of order; they are drawn into its system of framing with a curiosity for the object.

It is a curious choice that the centerpiece for Roldan’s Singapore show is an installation made from vestments gifted to the artist by an uncle priest. Presented as a triptych spanning some 10 feet, the vestments hang on a framework housing bottles with kristo and are studded with metal amulets spelling out the words “Rix Salvo Rix,” an extract from an oration colloquially translated as ‘King Hail King’ or ‘King Save Us King,’ a bastardization of Latin fusing Catholicism with animism. This piece is the pinnacle at which two ideas become one.

At the end of the day, we are left with a unique and deeply personal visual language built upon memory, (dis)association, and consideration. Is it sacred? Is it profane? The answer, like Roldan’s work itself, offers a fibrillation between the two states of thought coloured with the patina of global culture and Filipino kitsch. It is as seductive as its source.

About the Artist

About the Artists

Norberto Roldan (b. 1953, Roxas City) is a multimedia artist. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from the St. Pius X Seminary, a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Visual Communications from the University of Santo Tomas, Manila, and a Masters in Art studies at the University of the Philippines Diliman. Roldan is currently the artistic director of Green Papaya Art Projects, an alternative multidisciplinary platform which he co-founded in 2000.

He has represented the Philippines in various international exhibitions in Asia-Pacific, Europe, and the USA. He was represented in three landmark surveys of Southeast Asian contemporary art, including New Art from Southeast Asia by the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum (1992), Negotiating Home History and Nation: Two Decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia 1991–2011 by the Singapore Art Museum and most recently, No Country: Contemporary Art For South / Southeast Asia by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (2013). His works are included in collections worldwide, such as those of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, the Singapore Art Museum, the Deutsche Bank, the Banko Sentral ng Pilipinas, the San Miguel Corporation, the Ateneo Art Gallery, the Bencab Museum, the Carlos Oppen Cojuangco Foundation, the Artour Holdings Singapore, to name a few.

Related Exhibitions

About the Artists

About the Artist

Norberto Roldan (b. 1953, Roxas City) is a multimedia artist. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from the St. Pius X Seminary, a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Visual Communications from the University of Santo Tomas, Manila, and a Masters in Art studies at the University of the Philippines Diliman. Roldan is currently the artistic director of Green Papaya Art Projects, an alternative multidisciplinary platform which he co-founded in 2000.

He has represented the Philippines in various international exhibitions in Asia-Pacific, Europe, and the USA. He was represented in three landmark surveys of Southeast Asian contemporary art, including New Art from Southeast Asia by the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum (1992), Negotiating Home History and Nation: Two Decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia 1991–2011 by the Singapore Art Museum and most recently, No Country: Contemporary Art For South / Southeast Asia by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (2013). His works are included in collections worldwide, such as those of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, the Singapore Art Museum, the Deutsche Bank, the Banko Sentral ng Pilipinas, the San Miguel Corporation, the Ateneo Art Gallery, the Bencab Museum, the Carlos Oppen Cojuangco Foundation, the Artour Holdings Singapore, to name a few.

Related Exhibitions

Share